Mayowa Nwadike (b. 1998) manifests and embodies hybridization, globalization and transmigration of ideas through his stunning use of chiaroscuro and visually chimeric juxtapositions fixed in an always present past that, literally, faces a future. Nwadike is a Nigerian-born and based artist, and while his work is fixed in a place, a nation, a time of crisis, it also transcends the borders of nation, Continent and time. Nigeria is a place of great disparities, and the art world is made up of what Nwadike calls, “Gods and nobodies.” There is very little middle ground, institutional support is lacking, and often families, who are struggling with a very precarious present and future, discourage their children from pursuing the arts. Despite having his work, which he had hidden, burnt by his mother at an early age, Nwadike’s tenacious love of art, his technical skills and broad imagination combined to overcome familial, cultural and institutional hostility.

“He is a keenly aware of his process; he seems to be able to intuit what I am about to ask, answering it before it is asked. Perhaps this why his moniker is 6th. It stands for the sixth-sense, something that comes from beyond the realms of the clearly definable.“

“I was born into a family of four siblings; three brothers and a sister,” Nwadike says over a grainy WhatsApp connection. He is keenly aware of his process; he seems to be able to intuit what I am about to ask, answering it before it is asked. Perhaps this why his moniker is 6th. It stands for the sixth-sense, something that comes from beyond the realms of the clearly definable. “I grew up with my mom mainly, and my mom has very particular set of expectations for her children. For her, being an artist is not appropriate. We needed to study medicine; study medicine, I heard this over and over. Being a doctor here means you have both prestige and security. I wanted to be a pilot, an astronaut, I used to see the planes in the sky and dream of flying. That’s what inspired The Dream. You will note that the image is of a young boy, weighed down by a pilot’s helmet and wearing goggles that are far too large for him. Adult-sized dreams sat on my head, I suppose they still do.” The Dream captures the melancholy of childhood. A melancholy that comes from being precocious, other, and different. A waiting-in-childhood: a seriousness that children are all-too-often deprived of in the visual arts. Few artists, perhaps none, capture the dignified sadness of a waiting, contemplative and dissatisfied child the way Nwadike is able to.

His ability to capture the perplexing, perspicacious child comes from direct experience. “When I approached my year three examinations, I did very well in art, and my teacher told my mother that I would be good artist, yet my mother didn’t think it was practical. She actively discouraged it. I would sneak out of my house to see my art teacher at their studio. Sometimes I would get caught and whooped, and one time my art book was discovered and it was burnt. I was doing it [art] to ease the pressure. I am not the favorite child, and I didn’t have one of the best childhoods. I felt incredible depression. I did a drawing of my mom and that piqued her interest, but she said ‘you don’t want your dad to see this.’ I didn’t see myself as an artist.” His most tenebrist piece, also his most moving, is Step Into His Light. A boy’s face, faintly lit, quarter moon-like, stares, from complete darkness, upwards. As a Christian, this work has a double-meaning for Nwadike: it is both a theological commentary on the hope that Christ brings and a child looking from a dark, traumatic past toward an alter-future. A beam gently caresses the child’s face and hand, subtly illuminating the little Black boy’s features. His pupils gaze upwards, letting the viewer see the ‘whites of his eyes.’ What could be more intimate than this moment of pure consciousness grappling with a tenebroso juvenescence captured within the two-dimensional space of the pictorial plane?

“When just one charcoal pencil costs $1 USD, then the next month it’s $2 USD, and that’s just the pencil … and the people I am selling to often make around $100 USD a month, they just can’t afford to pay me even at cost.“

When Nwadike left home for university, he had a change: a change that comes from having a place of one’s own. Ah, space, even a small space, what graces it can afford! Acquiescing to the practical demands of his family, he enrolled in, and is currently finishing, a Bachelor’s Degree in Soil Sciences. We half-joking, half-seriously discussed how this might come in handy if he decided to do land-art in the future. “As soon as I arrived, I converted my room into a mini-studio. I use all my savings to buy art materials. For extra money I paint houses; sometimes, students ask that I design their rooms, and then I put that money right back into art supplies.” Art supplies are hard to find in Nigeria, and when he does find what he needs the prices seem to go up, sometimes doubling within a month or two. “When just one charcoal pencil costs $1 US dollar, then the next month it’s $2 US dollars, and that’s just the pencil … and the people I am selling to often make around $100 US dollars a month, they just can’t afford to pay me enough for the art to cover the costs of the materials.”

“Alongside his intimate and trenchant images of a childhood partly mutilated and mangled by his family, Nwadike, is visually crumpling the anti-Black, white delusions and hallucinations that are arguably — through enslavement, genocide and colonialism — at the core of socioeconomically structural expectations and limitations placed on young Nigerian men and boys.“

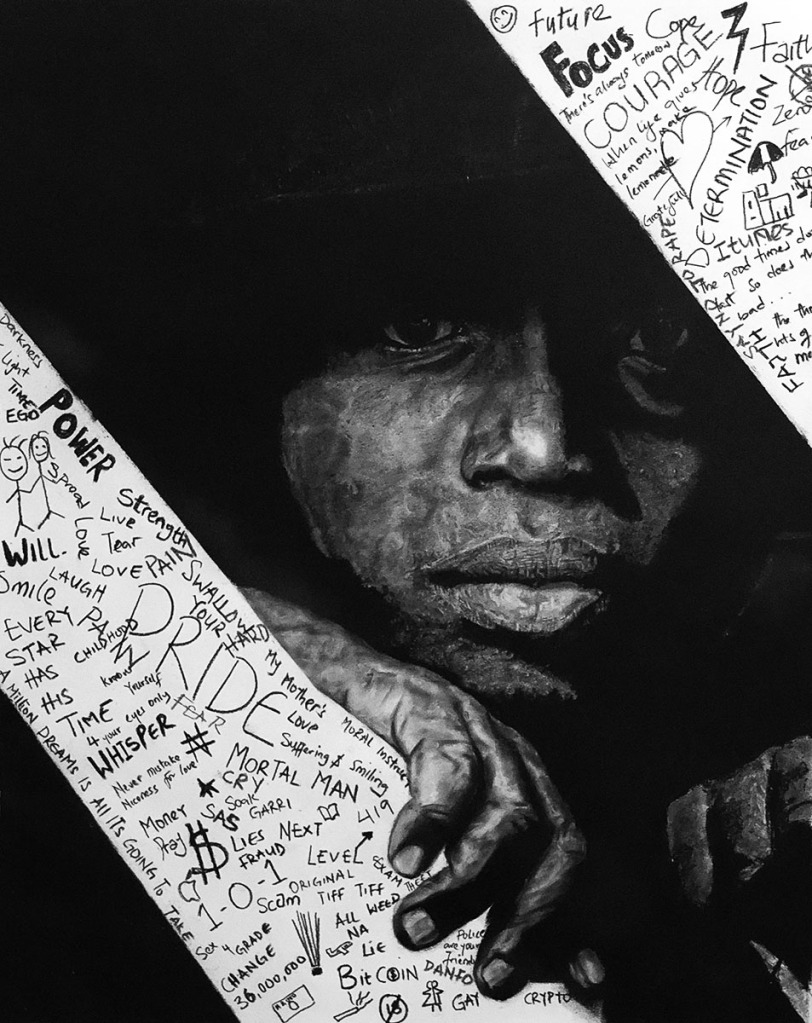

In his searing series, not yet fully released to the public, Black Power, Nwadike has Black male adolescents and men pushing through, or popping out, of Apartheid South Africa and USA Jim Crow symbols. The symbols are a paper tiger. The real power is in the Black people punching through oppressive, racist fictions. Yet, while racism is purely a symbolic, speculative fiction – one crafted out of white paranoia, wherein the paranoia is, borrowing from psychiatry, ‘a form of schizophrenia characterized by a slowly progressive deterioration of the personality, involving delusions and often hallucinations’ – it has a very real, material effect. Alongside his intimate and trenchant images of a childhood partly mutilated and mangled by his family, Nwadike, is visually crumpling the anti-Black, white delusions and hallucinations that are arguably — through enslavement, genocide and colonialism — at the core of socioeconomically structural expectations and limitations placed on young Nigerian men and boys.

Although the majority of Nwadike’s work is realistic, and often political, he recently began thinking about Abstract Expressionism; and even his AbEx piece, Beautiful Transitions, has a Caravaggio-quality to it: recherché dripped, dramatic, kinetic, and grand. Furthermore, the transition appears to be a wound; perhaps a surgical wound? Did the artist find himself removing something in order to enter/exit his metamorphosis? Nwadike treads carefully here, for the work is fresh and my inquiries are excited, “I suppose. Before, I thought that it [AbEx] was not disciplined, but as I began looking at these works closer, and especially in the creative process of making AbEx pieces, I realized it actually takes a great deal of discipline. And it allows the artist to experiment with themselves and the materials in a way that figurative drawing or painting does not. Yes, I am quite sure it has to do with a growing sense of freedom.” And perhaps a distance? And perhaps a room of his own? Is Nwadike finding that light he seeks? “Well, I want to keep expanding: mediums, methods, meanings. I am looking toward the future, like that boy. Despite the current situation here [in Nigeria], despite my history, despite the hardships, I will keep creating, experimenting, and developing my artistic capabilities.”

He is definitely an artist always.

. . .

Private collectors, interior designers, galleries and other institutions may contact Mr Nwadike regarding acquisition of works cited here, Nwadike’s full portfolio, including the Black Power series, & commissions. To submit an inquiry click here.

Featured Image: NAC NAS Not A Criminal Not A Saint, Pencil on Paper, 36″ x 24″ by Mayowa Nwadike

Reblogged this on Prison As Power.

LikeLike

Nwadike is such an awesome and realistic artist and I absolutely love what he does with his pencils. Like they say, every child is an artist and I’m happy he remained in his passions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Eromonsele Emmanuel, thank you. Your comment is appreciated.

Mayowa Nwadike is definitely a brilliant artist; one of the best figurative and abstract artists I have yet to find. I wish him well, and I look forward to following what seems to promise to be a long and fruitful career.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] revolutionary aspect of Abstract art, of abstraction in general, is re-emerging with artists from Mayowa Nwadike (b. 1998) and Green […]

LikeLike